For nearly 25 years, the North Rupununi District Development Board (NRDDB) in Guyana has been advocating for the protection of the North Rupununi Wetlands — the ancestral home and traditional ‘supermarket’ of the Makushi and Wapishana peoples. As development pressures increase across the Rupununi, the NRDDB has continued its efforts to empower communities to sustainably manage their landscapes. Recently, a series of training activities and follow-up visits were conducted in the communities of Kwaimatta, Rupertee, and Toka, under the Rights of Wetlands (RoW) initiative, aimed at supporting local conservation and development planning.

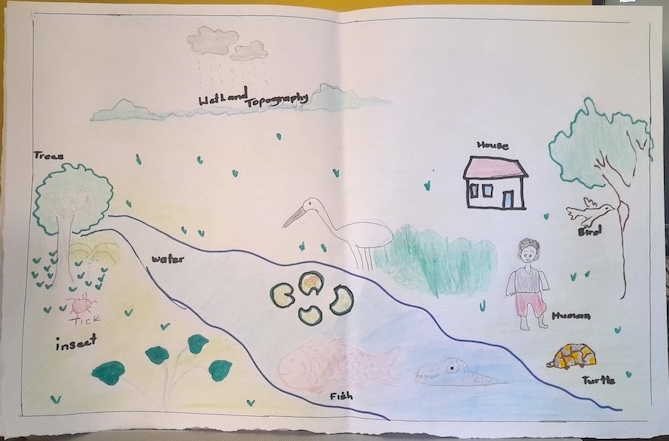

Community training: understanding wetlands and sustainable practices

Training sessions were initially held to deepen community knowledge about wetlands - their structure, function, and the services they provide. These discussions allowed villagers to connect daily activities such as farming, fishing, and construction with the health of the wetlands, fostering a greater understanding of how local actions impact the broader ecosystem. Armed with this new knowledge, community members began evaluating the kinds of information and skills they had/needed for improved wetland management. Priority areas identified included organic farming techniques, proper waste disposal methods, and sustainable construction practices.

Rupertee: from challenges to community-driven solutions

During visits to Rupertee, villagers shared the evolution of a once-modified creek, now a thriving reservoir attracting wildlife and providing recreational and subsistence benefits. However, development activities such as road construction and public infrastructure projects have introduced new challenges, including pollution, habitat fragmentation, and water source disruptions. To address these issues, the community devised practical solutions: reusing construction materials, creating better drainage systems, enforcing village rules on hunting and resource use. Additionally, Rupertee is making a participatory video titled ‘Using community development planning for sustainable use and conservation of the wetlands’ which will showcase how village sustainability planning has helped strengthen the community’s ability to prioritise activities focused on the long-term sustainability between the wetlands and people.

Kwaimatta: blending tradition and innovation

Kwaimatta village, rich in biodiversity and traditional ecological knowledge, faces similar challenges from climate change, pollution, and external development pressures. During our visits, villagers emphasized their reliance on medicinal plants, traditional crops, and sacred sites, underscoring the importance of preserving both natural and cultural heritage. One significant initiative in Kwaimatta is a tree planting project. This project’s initial focus was on using the exotic species Acacia and Eucalyptus, to grow timber species in more accessible areas to the community. However, discussions with the community encouraged them to shift towards favouring native species such as Crabwood and Water Cedar. Their participatory video ‘Growing timber for the future’ is being developed to share Kwaimatta’s experience and promote the use of important Indigenous species for reforestation and community forestry efforts. Although the origins of the tree planting is not local, there is strong community buy-in and it is hoped that it will become community owned as the village takes ownership and start pushing the activity forward on their own.

Toka: fire management for ecological and community safety

Toka village has identified uncontrolled savanna fires as a significant threat to both the wetlands and the safety of residents. Community members noted that wildfires destroy key vegetation, wildlife, and even homes, with climate unpredictability making fire risks harder to manage. The community also recognises that it will need to balance the use of its traditional knowledge to ensure that its developmental activities, like commercial farming of watermelon and eco-tourism, are sustainable and keep the wetlands intact. In response, Toka is aiming to develop a community owned fire management plan, combining traditional knowledge with modern planning approaches. The process will occur in two phases: (1) a small group going undertaking technical planning that will lead to a draft fire management plan, and (2) broader community consultation that would confirm these ideas and add any missing details. Their participatory video ‘Fire management planning in the community of Toka’ will document this process and serve as a guide for other communities facing similar risks. In doing this Toka envisions striking a balance between preserving the Rupununi Wetlands and sustaining the livelihoods of its residents. Initiatives like fire management planning are a testament to the community’s resilience and their commitment to safeguarding their environment for future generations.

Building a sustainable future

The experiences in Kwaimatta, Rupertee and Toka demonstrate that traditional knowledge and non-Indigenous planning approaches can come together to create lasting, community-driven solutions. Through training, participatory planning, and the development of local management strategies, the communities of the North Rupununi are showing that conservation and development are not mutually exclusive. By building on traditional knowledge, adopting sustainable practices, and strengthening governance structures, the North Rupununi communities are crafting a future where both people and wetlands can thrive. The work piloted here will offer valuable lessons for other communities across Guyana and beyond - that by investing in community knowledge, leadership, and resilience, and using the guiding principles of the Rights of Wetlands, we can safeguard our natural heritage for generations to come.